Within six days, Hurricane Katrina formed in the Atlantic Ocean, grew into a Category 5 storm and hit New Orleans, causing the deaths of nearly 1,400 people and obliterating homes, historic local businesses and colleges like Tulane University.

Twenty years later, Baylor College of Medicine continues to reflect on the special time when the Houston-area medical education community embraced its Louisiana neighbors and provided refuge from what is one of the costliest U.S. hurricanes on record (now tied with Hurricane Harvey).

On Aug. 31, 2005, the City of Houston was given 24 hours to prepare shelter space for nearly 75,000 citizens from New Orleans, according to the Houston-Galveston Area Council. The Houston Astrodome was the designated location to receive 25,000 evacuees who previously were housed in New Orleans’ Louisiana Superdome.

In emergency response, Baylor activated its physician network to see and treat evacuee patients at the Astrodome Clinic, which opened Sept. 1, one day after evacuees arrived in Houston. Starting out, four general medicine physicians worked 12-hour shifts in 20 exam rooms at the Astrodome, seeing evacuees who were already dealing with an onslaught of physical and mental health symptoms in the days after the storm.

In total, 1,000 doctors and residents from Baylor, now-UTHealth and private practices through the Harris County Medical Society treated adult and pediatric evacuees in the Astrodome Clinic.

But there were evacuees, maybe better referred to as academic refugees, who needed more than medical care; students from the Tulane University’s School of Medicine needed a place to study and complete their medical training since their campuses and other facilities were severely damaged. The final tally of net losses to Tulane totaled $90 million, mostly in heavy property damage, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Baylor opened its doors to Tulane’s faculty, medical and graduate students and residents to give them an opportunity to complete the academic year on schedule. Medical schools UTHealth, the University of Texas Medical Branch and Texas A&M Health (formerly Texas A&M Health Science Center) also took part in providing education space and resources.

Three years before his death at age 99, Dr. Michael E. DeBakey was one of the Baylor community members to welcome the students from New Orleans. A native of Lake Charles, Louisiana, DeBakey received his undergraduate degree and medical degree from Tulane.

First- and second-year Tulane students were based at the Cullen building at main Baylor with lessons taught by both Tulane and Baylor faculty. The third- and fourth-year medical students and residents trained at facilities operated by Baylor, UTHealth, UTMB and Texas A&M Health.

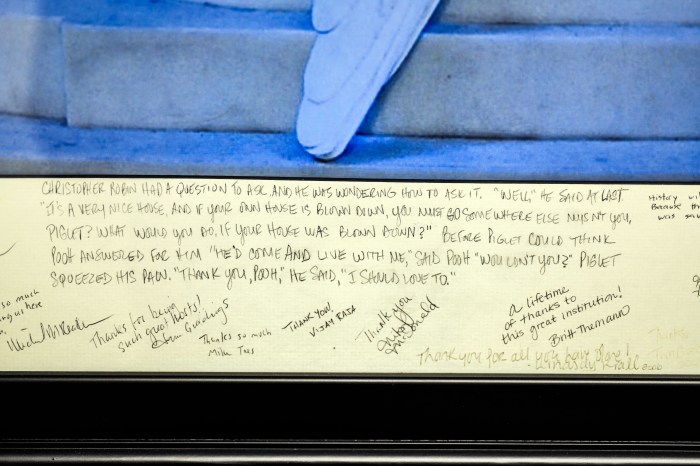

What made the situation more unique was the number of Baylor students and faculty who opened their homes to Tulane community members, providing a safe space for them to recover in the months following Katrina.

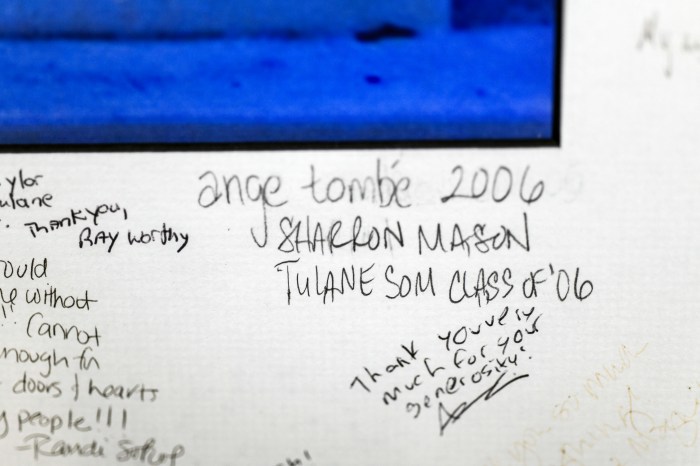

In March 2006, Tulane’s fourth-year students matched in Cullen Auditorium, took a celebratory group photo in front of the DeBakey Museum in Alkek and ate their weight in crawfish at a boil in the courtyard.

“During that year, we had Mardi Gras beads for any and all celebrations, a double Match Day at Baylor for fourth-year students from both schools and the creation of new friendships that continue 10 years later,” wrote Claire Bassett, chief communications officer at Baylor, for the 10th anniversary of Katrina in 2015. “This was Baylor College of Medicine at its best and forever bonded us to a sister medical school.”

By Julie Garcia

Compiled from reports housed in the Baylor College of Medicine Archives, Tulane University School of Medicine and the American Association of Medical Colleges